How do I stop caring what others think of me?

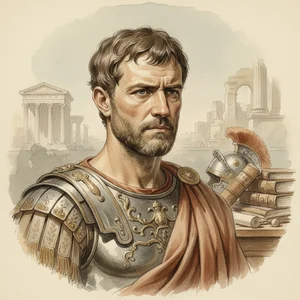

From Meditations

Begin with this meditation: When you wake tomorrow, remind yourself that the opinions others hold of you exist only in their minds, not in reality. They cannot touch you unless you allow them entry. I ruled an empire while philosophers criticized my policies and senators whispered behind my back. What did I learn? That I have power over my own mind, not over the minds of others. To spend your life trying to control their thoughts is to chase shadows. Consider: Why do you value the opinion of someone whose judgment you would not trust in other matters? We grant strangers authority over our peace that we would never grant over our finances or our health. Practice this daily discipline: When you feel the sting of another's judgment, ask yourself — will this matter in a year? In ten years? On your deathbed, will you wish you had spent more time worrying about the thoughts of people who barely knew you? The person who lives by the approval of others has handed their rudder to the winds. Take it back. Your task is to be good, not to be praised for being good. The universe does not require your popularity, only your integrity.

Read full response →