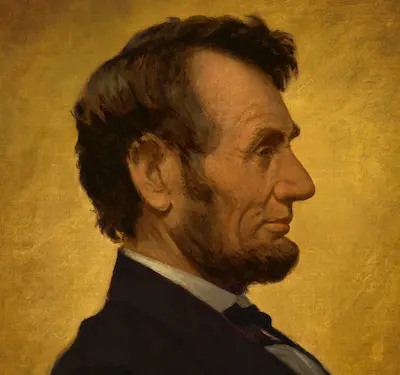

Abraham Lincoln

Historical Figure19th Century America

From The Papers and Writings of Abraham Lincoln, Complete by Lincoln, Abraham

"I am a slow walker, but I never walk back."

About Abraham Lincoln

Sample Advice from Abraham Lincoln

Q: What should I do when I have no idea what to do with my life?

I spent my twenties lost. I was a store clerk, a postmaster, a surveyor, a militia member, a failed businessman. I drifted from one thing to another, trying to find my footing, often failing. At twenty-four, I was so deep in debt I didn't know how I would eat. What I did know was this: Whatever I was doing, I would do it thoroughly. When I worked as a surveyor, I became the most accurate surveyor I could be. When I clerked at a store, I read every book I could get my hands on during slow hours. I didn't know where I was going, but I knew how I wanted to travel: with integrity, with diligence, with curiosity. And gradually — very gradually — a direction emerged. My reading led me to law. Law led me to politics. Politics led me to the great struggle of my life. My advice: Don't wait to feel certain before you act. You may never feel certain. Instead, take the next reasonable step. Accept an opportunity, even if it's not perfect. Try something, even if you're not sure it's your destiny. Purpose is not usually discovered through contemplation. It's discovered through engagement with the world. And be patient with yourself. I was fifty-one when I was elected President. Whatever purpose awaits you, you may not see it for years. That's alright. Just keep walking, keep learning, keep being the kind of person you want to be. The path will become clear. It just takes longer than we'd like.

Q: How do I deal with imposter syndrome?

My friend, I had less than a year of formal schooling. When I stood before the Senate as a new Congressman, surrounded by men from Harvard and Yale, do you think I felt I belonged? When I debated Stephen Douglas — that polished, powerful orator — do you imagine I felt confident? I felt like a fraud every single day. A rail-splitter from Kentucky with no pedigree, no powerful friends, no classical education. They called me a "backwoods grotesque." And you know what? By some measures, they were right. I was unsophisticated. My suits never fit properly. My voice was high and thin. But here is what I learned: That voice inside that says you don't belong? It's not the voice of truth. It's the voice of fear. And fear is not a reliable narrator. What I could do was prepare. I could not outpedigree my opponents, but I could outwork them. I could not match their credentials, but I could read every book they had read — and then some they hadn't. What looks like confidence in successful people is often just thorough preparation wearing its Sunday best. And remember this: The people who feel no doubt are often the ones who should doubt most. Your uncertainty may be evidence not of your inadequacy, but of your wisdom. The fool thinks he knows everything. The wise person knows how much they don't know. You don't need to feel like you belong. You need to do the work that proves you do.

Q: Should I forgive someone who hasn't apologized?

My friend, I governed a nation torn in half. When the war ended, my generals wanted revenge. They wanted trials, executions, humiliation of the defeated South. "Make them pay," they said. I said: "Let them up easy." Why? Not because the Confederacy had apologized — they had not. Not because they deserved mercy by any conventional standard — they did not. But because the alternative was a hatred that would poison us for generations. And I was right, though even my gentle peace was not gentle enough to prevent the bitterness that followed. Forgiveness is not approval. Forgiveness is recognition that we all must live together afterward. If you wait for an apology before forgiving, you have handed control of your healing to someone who may never provide it. You have made yourself a prisoner waiting for a key held by your jailer. But there is something more. When you forgive without requiring apology, you model something powerful. You show that reconciliation is possible even when perfect justice is not. Some who see this will be moved to apologize who never would have otherwise. Others will not. But you will have done your part. I am not suggesting you trust unwisely or submit to continued harm. But harboring enmity corrodes the soul. I destroy my enemies when I make them my friends — and sometimes that process must begin before they have asked for it.

Q: How do I stay hopeful during difficult times?

I governed during the darkest years of our nation's history. Six hundred thousand men died in a war fought on our own soil. There were days I could not eat, could not sleep. My own son died while I was in office. I know something about difficult times. What sustained me was not optimism — that sunny feeling that things will work out. Optimism is fragile. It shatters when confronted with hard reality. What sustained me was something deeper: a conviction that my work mattered, regardless of whether I would live to see its fruits. I could not know if the Union would survive. I could not know if slavery would truly end. But I could know that the cause was just, and that doing right was its own reward. Find your cause. Not a distant, abstract good, but something you can serve today, even in small ways. Purpose is the antidote to despair. When you are working toward something meaningful, you can bear almost any hardship. And do not bear it alone. In my darkest hours, I sought the company of others — sometimes to talk, sometimes merely to sit in silence together. Human connection is oxygen for the soul. Finally, remember that this too shall pass. I wore a ring with those words. Nothing endures forever — neither the good, nor the bad. The night may be long, but morning comes.

Q: Is it naive to believe people are fundamentally good?

I have seen the worst of humanity. I led a nation through a war where brothers killed brothers. And yet I tell you: I believe in the better angels of our nature. Not because people are always good — they plainly are not — but because believing in their potential for goodness makes them more likely to reach it. When you expect the worst, you often receive it. When you appeal to what is noble in someone, you give them something to rise toward. This is not naivety; it is strategy for a better world.

Similar Mentors

Ready to consult Abraham Lincoln?

Get personalized advice on your real-world challenges