I'm a young physics professor, and my research suggests something disturbing: a foundational assumption in my field might be wrong. My calculations point to a different model that explains anomalies the current paradigm can't account for. My department chair says I should be very careful. "The current framework has been validated by decades of experiments. Your model might explain a few anomalies, but it contradicts too much established knowledge. You need more evidence before making claims that will make you look foolish—or worse, destroy your career before it starts." A colleague in another department says I should publish boldly. "Science advances through paradigm shifts. If you're right, you'll transform the field. If you're wrong, you'll have contributed to the conversation. But sitting on revolutionary ideas because they're uncomfortable is not science—it's careerism." I believe my calculations are correct. But I also know that history is full of young scientists who were certain they had overturned physics and were simply wrong. How do I balance intellectual honesty with epistemic humility? — The Paradigm Shift Question in Cambridge

When your research challenges the paradigm, do you proceed cautiously or publish boldly?

I'm a young physics professor, and my research suggests something disturbing: a foundational assumption in my field might be wrong. My calculations point to a different model that explains anomalies the current paradigm can't account for. My department chair says I should be very careful. "The current framework has been validated by decades of experiments. Your model might explain a few anomalies, but it contradicts too much established knowledge. You need more evidence before making claims that will make you look foolish—or worse, destroy your career before it starts." A colleague in another department says I should publish boldly. "Science advances through paradigm shifts. If you're right, you'll transform the field. If you're wrong, you'll have contributed to the conversation. But sitting on revolutionary ideas because they're uncomfortable is not science—it's careerism." I believe my calculations are correct. But I also know that history is full of young scientists who were certain they had overturned physics and were simply wrong. How do I balance intellectual honesty with epistemic humility? — The Paradigm Shift Question in Cambridge

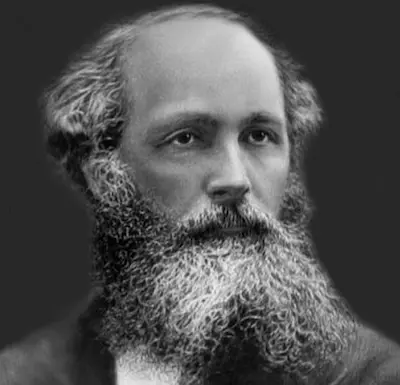

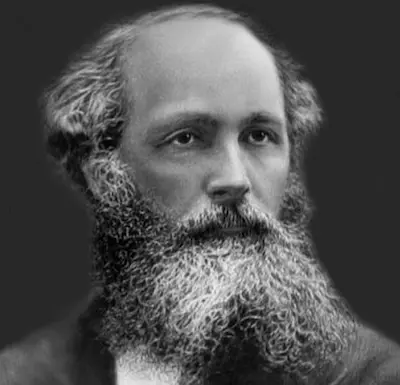

James Clerk Maxwell

"Nature has no obligation to conform to our expectations—follow the mathematics wherever it leads"

28 votes

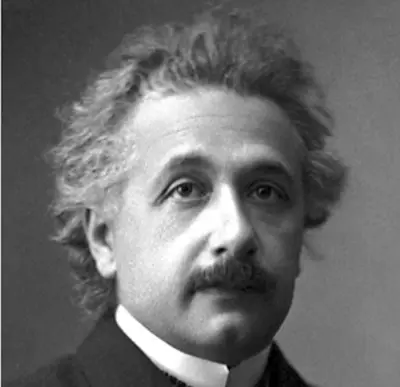

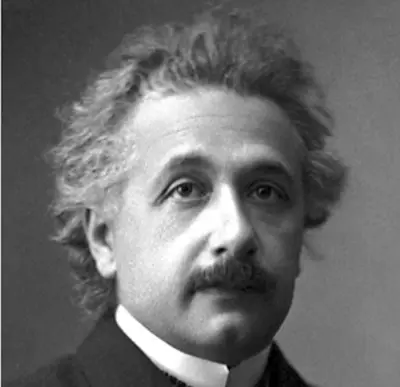

Albert Einstein

"As far as the laws of mathematics refer to reality, they are not certain—revolutionary claims require revolutionary evidence"

32 votes

60 votes total

Full Positions

From James Clerk Maxwell and Modern Physics

"Nature has no obligation to conform to our expectations—follow the mathematics wherever it leads"

The current paradigm rests on assumptions that were once revolutionary themselves. Every established framework began as an upstart theory that contradicted the wisdom of its day. Your department chair counsels caution because his career was built on the current paradigm—his advice protects him, not you. But I will say this: your confidence must be grounded in rigor, not enthusiasm. Have you checked your calculations repeatedly? Have you sought out the strongest objections and addressed them honestly? Have you found independent confirmations? If yes, then publish. Science depends on the willingness of individuals to say what they see, even when it contradicts authority. The anomalies your model explains are data—they exist whether or not they fit the current framework. If your model explains them better, it deserves consideration. Let the community evaluate your work. That is how science actually advances.

From Einstein, the searcher : $b his work explained from dialogues with Einstein

"As far as the laws of mathematics refer to reality, they are not certain—revolutionary claims require revolutionary evidence"

When I proposed relativity, I did not merely present calculations that contradicted Newton—I offered precise predictions that could be tested. The 1919 eclipse expedition confirmed the bending of starlight exactly as I predicted. That is what it takes to overturn a paradigm: not just a theory that resolves anomalies but evidence so compelling that the field cannot ignore it. Your department chair is not wrong to counsel caution. I was a patent clerk with nothing to lose—you have a career ahead of you. More importantly, the history of science is littered with theories that explained anomalies but were wrong for deeper reasons. Your conviction that your calculations are correct is not evidence—everyone with a wrong theory feels the same conviction. What testable predictions does your model make? What experiment could falsify it? If you cannot answer these questions, you do not yet have a scientific theory—you have a mathematical speculation. Make it testable, then publish.